Imagine a time when the cosmos was a tapestry of crystal spheres, meticulously arranged around a central Earth. For centuries, predicting the dance of the planets, the arrival of eclipses, or even just the correct date relied on complex calculations and tables passed down through generations. In the heart of medieval Europe, one such set of tables emerged that would dominate astronomical practice for over three hundred years: the Alfonsine Tables. They were not just a collection of numbers; they represented a monumental scientific undertaking, a bridge between ancient knowledge and the dawn of a new era of cosmic understanding, all set in motion by a visionary king.

A Universe Waiting to Be Charted

By the 13th century, European scholars largely relied on the astronomical framework established by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. His geocentric model, detailed in the Almagest, was a mathematical marvel, explaining the apparent motions of the stars and planets with epicycles and deferents. However, the tables derived from Ptolemy’s work, most notably the Toledan Tables compiled in Islamic Iberia around 1080, were showing their age. Tiny inaccuracies in the underlying parameters, compounded over centuries, meant that predictions were drifting further and further from observed reality. The positions of planets could be off by several degrees, a significant error when trying to cast accurate horoscopes (a major driver of astronomical work at the time) or determine religious festival dates. A fresh, more accurate set of astronomical tools was desperately needed, and the intellectual environment of Iberia, a melting pot of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim scholarship, was ripe for such a challenge.

The Wise King’s Grand Design

The impetus for this ambitious project came from Alfonso X, King of Castile, León, and Galicia, often known as Alfonso el Sabio (Alfonso the Wise). Reigning from 1252 to 1284, Alfonso was a remarkable patron of learning and the arts. His court in Toledo became a vibrant center of translation and scholarly activity, reviving and disseminating classical knowledge. He wasn’t just a passive funder; Alfonso took a keen personal interest in astronomy and astrology, understanding their practical importance for everything from agriculture to statecraft. He envisioned a comprehensive update to the existing astronomical data, one that would reflect the latest understanding and observational refinements, even if still grounded in the Ptolemaic system. This was not merely about correcting old numbers; it was about creating a definitive astronomical resource for his kingdom and beyond.

Gathering the Stars: The Toledo Team

To realize this grand vision, Alfonso X assembled a remarkable team of scholars, primarily based in Toledo. This group famously included Jewish astronomers Judah ben Moses Cohen and Isaac ibn Sid (also known as Rabbi Çag). These individuals were not just translators but skilled astronomers and mathematicians in their own right. While the project was predominantly a Latin Christian enterprise in its final output, the intellectual heritage drew deeply from Arabic and Hebrew astronomical traditions, which had preserved and advanced classical knowledge during Europe’s earlier medieval period. The task before them was immense. It involved not only studying existing texts, including Ptolemy’s Almagest and Arabic commentaries, but also, crucially, undertaking new observations to refine the fundamental parameters of the planetary models. This required instruments, patience, and a sophisticated understanding of spherical trigonometry and computational methods.

The project likely began shortly after Alfonso ascended to the throne in 1252 and took nearly two decades to complete, with the tables being finalized around 1272. The cost was said to be enormous, a testament to the King’s commitment. The scholars worked to determine the length of the tropical year with greater precision and to recalculate the mean motions (average speeds) and anomalies (deviations from average speed) of the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets. The epoch, or starting point for the tables’ calculations, was set to June 1, 1252, the coronation day of Alfonso X, symbolically linking this monumental scientific work to his reign.

Inside the Alfonsine Computations

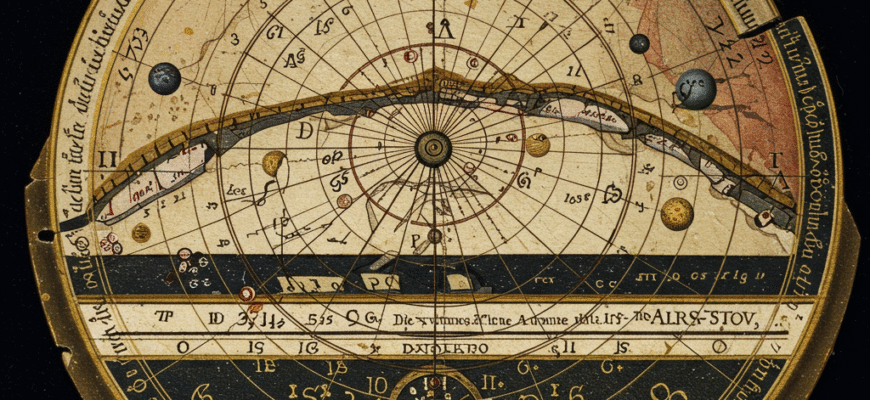

The Alfonsine Tables were, at their core, a set of pre-calculated numerical tables that allowed users to determine the celestial positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets for any given date, past or future. They were a practical tool, designed for computation rather than theoretical exposition. Their content was comprehensive for the era:

- Positions (longitude and sometimes latitude) of the Sun, Moon, and the five naked-eye planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

- Tables for predicting the timing and circumstances of solar and lunar eclipses.

- Data on the mean motions, equations of center, and other necessary corrections for each celestial body according to Ptolemaic theory.

- Information for calculating planetary conjunctions, oppositions, and other significant astronomical configurations.

- Calendrical tables for converting between different eras and for determining dates.

- Tables of fixed stars, updating Ptolemy’s star catalog, often incorporating precession.

Structurally, the tables provided mean positions for a specific starting date (the epoch) and then offered additive or subtractive values (equations) to correct these mean positions for the actual date required. This methodology, inherited from Ptolemy, involved complex geocentric models with epicycles, deferents, and equants. While the Alfonsine Tables did not propose a new cosmology—they were firmly Ptolemaic—they offered updated parameters derived from new observations and extensive recalculations. The values for the length of the year and the rate of precession of the equinoxes were among the key updates that distinguished them from earlier tables. They were typically presented in Latin, the scholarly language of Europe, and used sexagesimal (base-60) notation for angles and time, a system with ancient Babylonian roots.

The Alfonsine Tables were formally commissioned by King Alfonso X of Castile around 1252, with the dedicated work of astronomers like Judah ben Moses Cohen and Isaac ibn Sid. Completed in the early 1270s, these tables provided a comprehensive dataset for calculating planetary positions and predicting eclipses within the Ptolemaic geocentric framework. Their primary reference date, or epoch, was set to the beginning of Alfonso X’s reign, underscoring his royal patronage. These tables quickly became the European standard for astronomical calculations.

Centuries of Dominance

Once completed, the Alfonsine Tables began a slow but steady dissemination across Europe. Initially, this was through expensive, hand-copied manuscripts. Despite their cost and the labor involved in reproduction, their utility ensured their spread. Universities, which were beginning to flourish, adopted them for teaching astronomy. Astrologers, whose practice was deeply intertwined with astronomy, relied heavily on them for casting horoscopes, which required precise planetary positions. The tables also found use in more mundane but vital tasks like calendar reform, timekeeping, and, to some extent, navigation, although dedicated navigational tables would evolve later. For over two hundred years, if an astronomer, scholar, or astrologer in Europe needed to know where Mars would be or when the next lunar eclipse was due, they would almost certainly turn to a copy, or a derivative, of the Alfonsine Tables. They became the de facto astronomical standard, replacing the older Toledan Tables.

The Printed Revolution and the Tables

The invention of printing with movable type in the mid-15th century dramatically accelerated the spread and accessibility of the Alfonsine Tables. One of the earliest and most famous printed editions was produced by Erhard Ratdolt in Venice in 1483. This made the tables available to a much wider audience than ever before, further cementing their authority. Even astronomers who would later challenge the geocentric model, such as Nicolaus Copernicus, initially learned their craft and performed their calculations using the Alfonsine Tables. Copernicus himself owned a copy of the 1492 Venice edition, and while he found inaccuracies and was developing his heliocentric theory, the Alfonsine Tables provided a baseline and a computational framework against which new ideas could be tested. They were, in essence, the common language of European astronomy well into the 16th century.

The Cracks in the Crystal Spheres

Despite their remarkable longevity and utility, the Alfonsine Tables were not perfect, nor could they be. Their fundamental limitation was their adherence to the Ptolemaic geocentric model. While ingenious, this model was ultimately a description of appearances rather than physical reality, and it required increasingly complex adjustments to match observations. Over time, even the refined parameters of the Alfonsine Tables began to accumulate errors. The motions of the planets are incredibly complex, and the simplified models, even with their epicycles, couldn’t capture all the nuances. By the 15th and 16th centuries, astronomers were noting discrepancies between predictions made using the tables and actual observations. This growing awareness of their shortcomings helped fuel the search for better models and more accurate data. The very precision the Alfonsine Tables aimed for, and largely achieved for their time, eventually highlighted the flaws in the underlying cosmological theory they served.

A Lasting Celestial Legacy

The Alfonsine Tables were eventually superseded, first by the Prutenic Tables (1551) of Erasmus Reinhold, which were based on Copernicus’s heliocentric model, and later by Johannes Kepler’s incredibly accurate Rudolphine Tables (1627), derived from Tycho Brahe’s meticulous observations and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. Yet, the significance of the Alfonsine Tables in the history of science remains immense. They represent a high point of medieval European scientific endeavor and a critical moment in the transmission and development of astronomical knowledge. They demonstrate the fruitful interaction of cultures in medieval Iberia and the profound impact of royal patronage on scientific advancement. For nearly three centuries, they were the bedrock of European astronomy, guiding observations, informing theories, and training generations of scholars. The Alfonsine Tables were more than just numbers; they were a landmark, a testament to humanity’s enduring quest to understand its place in the cosmos, and a crucial stepping stone towards the scientific revolution.