The late 19th century buzzed with a new kind of energy. Science was on the march, and photography, a relatively young marvel, promised to unlock secrets the human eye alone could never grasp. In the realm of astronomy, this new tool sparked a truly audacious dream: to create a definitive, photographic map of the entire celestial sphere. This grand endeavour, known as the Carte du Ciel, or “Map of the Sky,” was born of immense optimism and international cooperation, yet it would ultimately become a monumental testament to the perils of overambition.

A Celestial Vision Forged in Paris

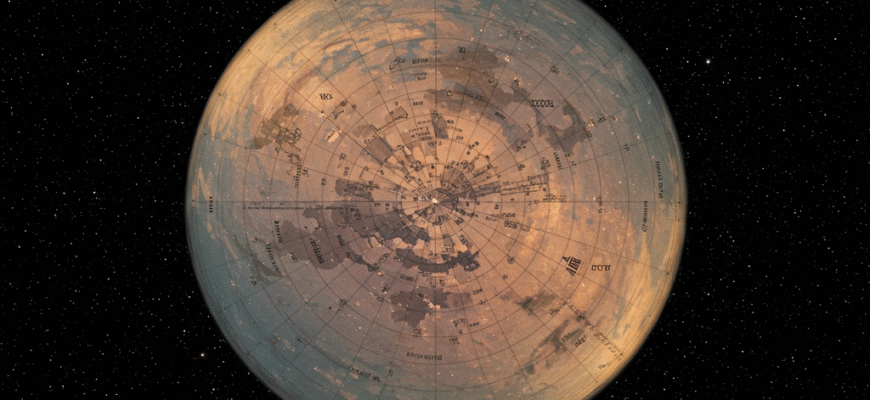

The year was 1887. Astronomers from across the globe converged in Paris, their minds alight with the possibilities offered by the dry photographic plate. Spearheaded by the director of the Paris Observatory, Amédée Mouchez, the Astrographic Congress laid out a breathtakingly ambitious project. The plan was twofold: first, to create the Astrographic Catalogue, a meticulous listing of the positions and magnitudes of millions of stars down to the 11th or 12th magnitude. Second, and far more visually ambitious, was the Carte du Ciel itself – a photographic atlas of the entire sky, showing stars down to the 14th magnitude. This was not just a catalogue of numbers; it was meant to be a permanent, visual record of the heavens at a specific epoch.

To achieve this, the sky was divided into zones, with 18 (eventually 20) observatories around the world volunteering to photograph their assigned sections. Standardized astrographic telescopes, with an aperture of about 13 inches (33 cm) and a focal length of 11.25 feet (3.43 m), were to be used, ensuring uniformity. Each photographic plate would cover a square of two degrees by two degrees of the sky. The sheer scale was unprecedented.

The Immense Labor of Charting the Stars

Capturing the sky was only the beginning. For the Astrographic Catalogue, each plate, once developed, had to be painstakingly measured. This involved identifying hundreds, sometimes thousands, of star images on a single plate and determining their precise coordinates relative to each other and to known reference stars. This colossal task often fell to teams of “computers,” predominantly women, who spent countless hours peering through measuring engines. The calculations to convert these measurements into celestial coordinates were equally laborious in an era before electronic computers.

For the Carte du Ciel chart plates, the process was even more demanding. These required much longer exposures – typically 40 minutes, an hour, or even more, compared to the shorter exposures for the catalogue plates. The goal was to capture fainter stars, creating a richer, deeper image. Guiding the telescope perfectly for such extended periods was a significant challenge, and any slight error could ruin a plate. Then came the issue of reproduction and distribution of these charts. The original vision was for engraved reproductions, an expensive and time-consuming process.

The sheer volume of work was staggering. It was estimated that over 22,000 photographic plates would be needed for full sky coverage for each part of the project. Each plate required careful exposure, development, measurement, and reduction. This process demanded immense human and financial resources over many decades, far exceeding initial projections.

Mounting Challenges and Fading Dreams

The initial enthusiasm that fueled the Carte du Ciel began to wane as the decades stretched on. Several formidable challenges contributed to the project’s struggles, particularly for the more ambitious Chart component.

The Tyranny of Time and Resources

The sheer scale of the undertaking was consistently underestimated. What was initially envisioned as a project spanning perhaps ten to fifteen years dragged on for much, much longer. Funding became a persistent issue for many participating observatories, especially as other astronomical priorities emerged. The meticulous work of measuring and reducing plates was slow and expensive. Many observatories fell behind schedule, some significantly so.

The long duration also meant that key personnel retired or passed away, leading to losses of expertise and momentum. Furthermore, the world did not stand still. Two World Wars ripped through the 20th century, severely disrupting international collaboration, diverting resources, and, in some cases, damaging observatories or their records.

Despite the immense difficulties, the spirit of international scientific collaboration was a hallmark of the Carte du Ciel’s early years. Observatories from Santiago to Sydney, from Paris to Algiers, committed to their allocated sky sections. This global effort laid groundwork for future large-scale astronomical surveys and demonstrated a powerful model for scientific cooperation.

Technological Hurdles and Shifting Paradigms

While photography was a revolutionary tool, 19th-century photographic technology had its limitations. The quality of photographic plates could be inconsistent. Emulsions varied, and plates were susceptible to damage or degradation over time. The very act of measuring tiny star specks on glass was prone to human error and fatigue.

Moreover, the scientific utility of the Carte du Ciel charts, as originally conceived, began to be questioned. The long exposures required to capture stars down to the 14th magnitude meant that the images were incredibly dense with stars. For some regions, particularly near the Milky Way, the charts were so crowded that they became difficult to interpret or use for visual searches of specific objects like asteroids or variable stars. Reproducing these detailed plates faithfully and affordably also proved a major stumbling block. The initial idea of engraved copper plates was largely abandoned due to cost and time, and direct photographic copies had their own issues with quality and permanence.

As the 20th century progressed, astronomical techniques continued to evolve. Newer, faster photographic emulsions became available, and eventually, electronic detectors like CCDs would revolutionize astrometry and imaging, offering far greater sensitivity and dynamic range than the glass plates of the Carte du Ciel era. The fixed-epoch nature of the Carte du Ciel also meant its data, especially for proper motions, would need constant updating – a task that the original project structure was not well-equipped to handle continuously.

A Tale of Two Sky Maps: Catalogue vs. Chart

It is crucial to distinguish between the two main components of the Astrographic Project, as their fates were quite different. The Astrographic Catalogue (AC), despite the enormous effort it entailed, was largely a success. By the mid-20th century, most of the participating observatories had completed their measurements and published their catalogues. These provided positions and magnitudes for over 4.6 million stars. For decades, the AC was a fundamental reference for astrometry, stellar proper motions, and galactic structure studies. It provided a dense network of reference stars across the sky, invaluable for calibrating other observations and for discovering stars with high proper motion.

The Carte du Ciel (the Chart itself), however, tells a different story. This photographic atlas, intended to show stars down to the 14th magnitude, was the component that truly faltered. While many thousands of chart plates were exposed, only a fraction were ever published or reproduced in a systematic way. The immense cost, the technical difficulties of reproduction, the sheer density of stars on the plates, and the waning interest over time meant that the grand vision of a complete, uniform photographic map of the heavens remained largely unfulfilled. The original goal of creating a readily usable atlas for astronomers worldwide was never fully realized for the Chart component.

Legacy of an Unfinished Dream

So, was the Carte du Ciel an unmitigated failure? Not entirely. While the Chart component fell far short of its lofty goals, the project as a whole left a significant legacy. The Astrographic Catalogue, as mentioned, was a monumental achievement that served astronomy well for many decades. The vast collection of photographic plates, many of which still exist in observatory archives, represents a unique historical record of the sky at the turn of the 20th century. These plates have proven valuable for long-term studies, such as searching for variable stars or tracking the past positions of objects.

The project also spurred advancements in astronomical instrumentation, photographic techniques, and methods for large-scale data reduction. The challenges encountered provided hard-won lessons in the management of massive international scientific collaborations – lessons that would inform future sky surveys. Perhaps most importantly, the Carte du Ciel embodied a bold spirit of inquiry, a desire to systematically map and understand our universe on an unprecedented scale. It highlighted the need for careful planning, realistic assessment of resources, and adaptability in the face of technological evolution.

The Carte du Ciel stands as a stark reminder that even with noble scientific goals and international cooperation, overreach can cripple a project. The ambition to create a perfect, all-encompassing map with the technology of the day proved too great a hurdle. It underscores the importance of defining achievable milestones and being prepared for unforeseen complexities in long-term scientific endeavors, especially those spanning generations.

In the end, the Carte du Ciel may not have delivered the complete “Map of the Sky” its founders envisioned, but it etched its own story into the annals of astronomy – a story of grand ambition, painstaking labor, international endeavor, and the enduring human quest to chart the cosmos. It was a dream that, even in its partial incompletion, pushed the boundaries of what was thought possible and left behind a foundation upon which future celestial cartographers would build.