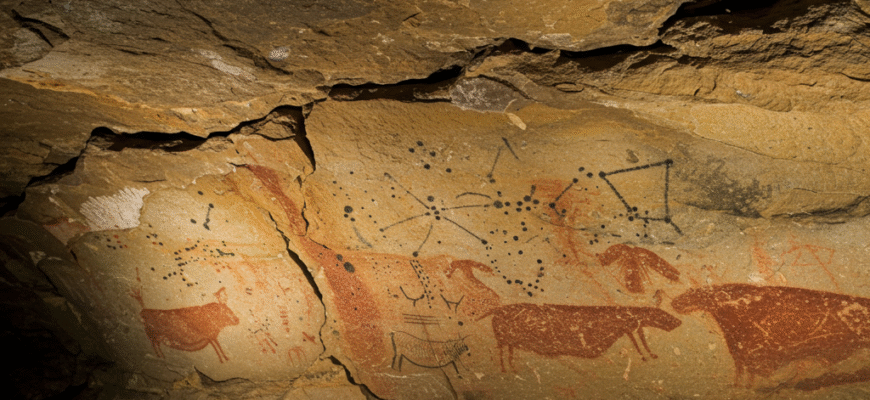

The deep, echoing chambers of prehistoric caves hold more than just stunning depictions of bison, horses, and mammoths. For decades, a tantalizing question has lingered among archaeologists and astronomers: could these ancient artists, living tens of thousands of years ago, have also been charting the night sky? The idea that dots, lines, and even animal figures might represent constellations or significant celestial events is a captivating one, suggesting a far more sophisticated understanding of the cosmos by our ancestors than previously imagined.

Whispers from the Stone Age Sky

When we gaze upon the masterpieces of Lascaux, Altamira, or Chauvet, the immediate impression is often one of hunting magic, shamanistic rituals, or simply an artistic appreciation for the animal world that sustained early humans. These interpretations are well-established and hold considerable weight. Yet, an undercurrent of inquiry pushes further, asking if the patterns of dots often accompanying these figures, or the specific arrangements of the animals themselves, might have a dual meaning, encoding astronomical knowledge critical for survival or spiritual life.

The night sky was, after all, the first calendar, the first clock, and the first map for ancient peoples. The predictable cycles of the sun, moon, and stars would have been crucial for tracking seasons, predicting animal migrations, and perhaps even for navigation across vast, unmarked landscapes. It’s not a giant leap to consider that societies so intimately connected with nature would also pay close attention to the celestial sphere and attempt to record its patterns.

Celestial Canvases? Famous Cases Under Scrutiny

Several specific sites and theories have become central to the debate about prehistoric star maps. These interpretations, while often compelling, are also fraught with challenges.

The Lascaux Enigma

Perhaps the most famous example comes from the Lascaux Cave in France, with art dating back around 17,000 years. In the magnificent Hall of the Bulls, one particular section has drawn intense scrutiny. A prominent bull figure (aurochs) appears near a cluster of dots. Researcher Dr. Michael Rappenglück, among others, has proposed that this bull represents the constellation Taurus, with the cluster of dots signifying the Pleiades star cluster, often referred to as the Seven Sisters. The visual similarity is striking, especially when considering how these celestial patterns would have appeared in the Paleolithic sky.

Furthermore, near the bull’s shoulder, another set of dots has been interpreted as representing part of the constellation Orion. Elsewhere in Lascaux, in a section known as the Shaft of the Dead Man, a scene depicting a disemboweled bison, a bird-headed man, and a bird on a stick has been linked by some researchers to the Summer Triangle (the stars Vega, Deneb, and Altair), suggesting a possible depiction of a celestial event or a seasonal marker. The arguments often involve using planetarium software to reconstruct the prehistoric night sky and find alignments.

It is crucial to remember that interpreting ancient art is inherently complex. While alignments with star patterns can be found, proving intentionality across millennia is exceptionally difficult. Many arrangements could be coincidental, or their primary meaning might lie in entirely different cultural or symbolic realms.

Göbekli Tepe: Pillars of the Cosmos?

While not strictly cave paintings, the megalithic site of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, dating back around 11,600 years, offers related insights into early astronomical understanding. Its T-shaped pillars are intricately carved with animals. One particular pillar, Pillar 43 (often called the “Vulture Stone”), has been interpreted by some researchers, like Martin Sweatman and Dimitrios Tsikritsis, as depicting a date stamp for a cataclysmic event, possibly the Younger Dryas impact event. They argue that the animal carvings correspond to astronomical constellations and that their arrangement records a specific moment in time, referencing precession of the equinoxes.

This theory suggests that the people of Göbekli Tepe were not only observing the stars but were also capable of understanding complex astronomical phenomena like precession, using animal symbols as celestial markers. However, this interpretation is highly debated within the archaeological community, with many experts favoring symbolic or shamanistic explanations for the carvings.

Other Potential Sites and Symbols

The search for ancient star maps extends beyond Lascaux and Göbekli Tepe. Claims have been made for astronomical interpretations at numerous other sites:

- El Castillo Cave, Spain: A panel of dots in the “Gallery of Discs” has been suggested by some to represent the Corona Borealis constellation, dating back possibly 34,000 years.

- Chauvet Cave, France: The intricate arrangements of dots and animal figures, dating back over 30,000 years, have also invited astronomical speculation, though less specific claims have gained traction.

- Cosquer Cave, France: This underwater cave contains engravings of auks, which some have linked to representations of the Pleiades or other celestial bodies, aligning with their seasonal appearance or disappearance.

The challenge with many of these interpretations lies in the sheer number of dots and abstract marks present in cave art. With enough data points, it’s possible to find patterns that resemble almost anything if one looks hard enough – a phenomenon known as pareidolia.

The Art of Interpretation: Seeing Stars or Seeing What We Want?

The core of the debate rests on a few fundamental challenges. Firstly, proving intent is incredibly difficult. We cannot ask the artists what they meant. While a pattern of dots might resemble the Pleiades to our modern eyes, conditioned by centuries of Greek astronomical tradition, it could have meant something entirely different to a Paleolithic hunter-gatherer. It might have represented a group of huts, a tally of kills, or a purely abstract decorative motif.

Secondly, the accuracy of dating both the art and the proposed celestial events is critical. While dating techniques have advanced significantly, precise correlations can still be elusive. The sky changes over millennia due to precession, so any proposed star map must align with the sky as it was at the time the art was created.

Thirdly, alternative explanations often hold strong. The primary function of these animals could indeed be related to ensuring successful hunts, placating animal spirits, or documenting tribal myths and totems. The astronomical layer, if it exists, might be secondary or symbolic, rather than a literal attempt at cartography.

Skeptics also point out that the human brain is wired to find patterns. Given the thousands of stars visible to the naked eye and the myriad of dots and abstract symbols in cave art, coincidental alignments are statistically probable. To overcome this, proponents need to demonstrate patterns that are too consistent or too complex to be mere chance.

Why Would They Chart the Heavens?

If prehistoric people were indeed depicting star maps, why would they do so? The motivations could be multifaceted:

- Timekeeping and Calendrics: The rising and setting of specific stars or constellations mark the passage of seasons. This would be invaluable for knowing when to expect animal migrations, when certain plants would be ready for harvest, or when to move to different seasonal camps. The Pleiades, for example, have been used as a seasonal marker by cultures worldwide.

- Navigation: While perhaps less critical for cave dwellers who might have had established territories, knowledge of the stars is fundamental for navigating over longer distances, especially in featureless terrain or at night.

- Mythology and Cosmology: The stars have always been a source of wonder and a canvas for storytelling. Constellations could have been woven into origin myths, heroic tales, or the spiritual beliefs of the community, providing a framework for understanding the cosmos and humanity’s place within it.

- Ritual and Shamanism: Celestial events might have been tied to specific rituals. Shamans, as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual worlds, might have used star knowledge in their practices, perhaps interpreting celestial phenomena as omens or messages from spirits.

The sky was a constant, predictable, yet ever-changing presence in the lives of ancient peoples. It provided light, marked time, and perhaps offered a sense of order in a world that could often be chaotic and dangerous. To represent it, even symbolically, would be a natural extension of their engagement with their environment.

The Ongoing Quest for Answers

The question of whether prehistoric cave paintings depict accurate star maps remains largely unresolved, a fascinating intersection of art, archaeology, and astronomy. Archaeoastronomy, the discipline dedicated to studying the astronomical knowledge of past cultures, continues to develop new methods and re-examine old evidence.

What is generally accepted is that prehistoric peoples possessed a keen awareness of their celestial environment. They undoubtedly observed the movements of the sun, moon, and stars and integrated this knowledge into their lives. Whether this translated into deliberate, recognizable “maps” on cave walls is where the consensus frays.

Perhaps the definition of “accurate star map” needs to be flexible. It’s unlikely these were precise cartographic tools in the modern sense. Instead, they might have been symbolic representations of important celestial features or events, mnemonics for stories, or markers of sacred times. The animals themselves, often rendered with such care and dynamism, could have been the earthly counterparts to celestial figures, linking the world below with the cosmos above.

Ultimately, the allure of these ancient images lies in their ability to connect us to a distant past, offering glimpses into the minds of people who, despite the vast gulf of time, shared our human capacity for observation, creativity, and the profound desire to understand the universe. Whether or not every cluster of dots is a lost constellation, the paintings themselves are a testament to a rich inner world, one that surely looked up in wonder at the star-dusted night.