The late nineteen fifties thrummed with a nervous energy. The Cold War was not just a terrestrial standoff; it had blasted skyward. When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957, the beeping satellite sent ripples of shock and a dawning sense of urgency across the United States. It was more than just a technological marvel; it was a stark challenge. America, a nation priding itself on innovation, found itself looking up at a competitor achievement. The response had to be swift, decisive, and bold. Thus, from this crucible of geopolitical tension and nascent technological ambition, Project Mercury was born – an American audacious first foray into the realm of human spaceflight.

Forging a Path to the Stars

In 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established, a civilian agency tasked with spearheading American space endeavors. High on its agenda was putting a human into Earth orbit. Project Mercury, officially approved that same year, had clear, if daunting, objectives. First, and foremost, was to achieve orbital flight with an astronaut. Second, the project aimed to investigate the ability of an astronaut to not just survive, but function effectively within the alien environment of space. Finally, and critically, the mission required the safe recovery of both the astronaut and the spacecraft. These goals were simple to state, yet monumental to achieve given the technology of the era.

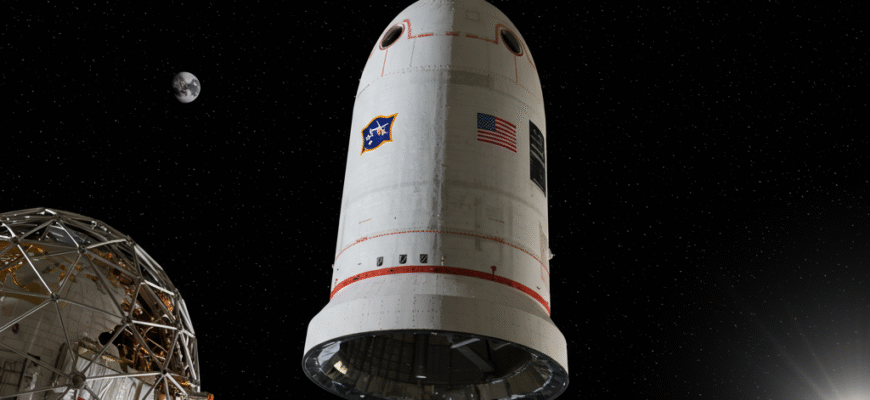

The Mercury Capsule: A Snug Ride to Orbit

The Mercury spacecraft itself was a marvel of compact engineering, often described as something one wore rather than flew. It was a small, cone-shaped capsule, just over six feet long at the base and weighing around 1.5 tons fully loaded. Designed for a single occupant, it was crammed with instrumentation, life support systems, and navigational aids. Key features included a beryllium heat shield to withstand the fiery temperatures of atmospheric re-entry, an escape tower designed to pull the capsule away from a failing launch vehicle, and small thrusters for attitude control in orbit. The astronauts, in a tradition that would continue, gave their capsules personal names: Freedom 7, Liberty Bell 7, Friendship 7, Aurora 7, Sigma 7, and Faith 7.

The Chosen Few: The Mercury Seven

Who would dare to pilot these experimental craft? NASA sought individuals with extraordinary courage, skill, and resilience. The call went out to military test pilots, men accustomed to pushing the boundaries of aviation and facing extreme danger. After a grueling selection process, seven men were chosen in April 1959: Alan Shepard, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, John Glenn, Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra, Gordon Cooper, and Deke Slayton (though Slayton was later grounded due to a heart condition, he would eventually fly on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project). These men, dubbed the “Mercury Seven,” instantly became national heroes, embodying the “Right Stuff” – a blend of bravery, skill, and cool-headedness under pressure. They were not just pilots; they were symbols of American aspiration and determination.

The selection criteria for the Mercury astronauts were incredibly stringent. Candidates had to be no older than 40, shorter than 5 feet 11 inches (due to capsule constraints), possess a bachelor degree or equivalent in engineering or a physical science, and be graduates of a military test pilot school with at least 1500 hours of jet flight time. This ensured a pool of highly experienced individuals capable of handling unprecedented situations.

Paving the Way: Uncrewed Missions and Primate Pioneers

Before risking human lives, NASA conducted an extensive series of uncrewed test flights. These were essential for validating the spacecraft systems, launch vehicles, and the global tracking network. Missions like Big Joe and Little Joe tested the aerodynamic shape of the capsule and abort systems. The Mercury-Redstone (MR) and Mercury-Atlas (MA) rockets, adapted from military missiles, underwent rigorous trials to ensure their reliability. Among the most famous of these preliminary flights were those carrying primate passengers. Ham the Chimp successfully flew a suborbital trajectory aboard MR-2 in January 1961, performing simple tasks that demonstrated an organism could function during spaceflight. Later, Enos the Chimp completed two orbits aboard MA-5 in November 1961, further building confidence before human orbital attempts.

First Leaps: Shepard and Grissom

The moment America had been waiting for arrived on May 5, 1961. Strapped into his capsule, Freedom 7, atop a Redstone rocket, Alan Shepard became the first American in space. His suborbital flight lasted just over 15 minutes, reaching an altitude of 116 miles. Though brief, it was a monumental achievement, proving an American could indeed venture into the cosmos and return safely. The nation erupted in celebration. Shepard famously exclaimed, “What a beautiful view!” and “Everything A-OK!” during his brief sojourn.

Two months later, on July 21, 1961, Gus Grissom piloted Liberty Bell 7 on a similar suborbital flight. While the flight itself was successful, disaster nearly struck after splashdown. The hatch of Liberty Bell 7 prematurely blew, and the capsule began to fill with water. Grissom scrambled out and was rescued by helicopter, but the spacecraft sank to the ocean floor, only to be recovered decades later. This incident highlighted the inherent dangers and the steep learning curve of early space exploration.

Circling the Globe: Glenn and Beyond

The next major milestone was orbital flight. On February 20, 1962, John Glenn, aboard Friendship 7, launched on an Atlas rocket and became the first American to orbit the Earth. His five-hour, three-orbit mission captivated the world. Glenn reported observing “fireflies” – small, luminous particles outside his window (later thought to be ice crystals or tiny pieces of paint or insulation) – and faced a tense period when mission control suspected his capsule heat shield might be loose. The decision was made to leave the retro-rocket pack attached during re-entry, hoping it would help hold the shield in place. Glenn returned a hero, his flight a resounding success that leveled the playing field with the Soviets, who had already achieved orbital flight with Yuri Gagarin.

Three more orbital flights followed. In May 1962, Scott Carpenter piloted Aurora 7 for a three-orbit science-focused mission. His flight experienced some operational difficulties, including higher-than-planned fuel consumption for maneuvering and a landing far off target, leading to a tense wait for recovery. However, valuable scientific data was gathered.

Wally Schirra, in Sigma 7 (October 1962), executed what was often called a “textbook flight.” His six-orbit mission focused on engineering evaluations of the spacecraft, conserving fuel meticulously and demonstrating precise control. The flight by Schirra was a testament to the growing maturity of the Mercury systems and operational procedures.

The final Mercury mission, Faith 7, was piloted by Gordon Cooper in May 1963. It was the longest of the series, lasting over 34 hours and completing 22 orbits. The flight by Cooper pushed the Mercury hardware to its limits. He became the first American to sleep in orbit and had to perform a manual re-entry after several automated systems failed, showcasing the critical importance of pilot skill. His successful return marked a triumphant conclusion to Project Mercury.

Technological Strides and Unseen Networks

Project Mercury was not just about the astronauts and their capsules; it spurred significant technological advancements. The Redstone and Atlas rockets, initially designed as ballistic missiles, were human-rated through rigorous testing and modification. This process of adapting existing military hardware for peaceful space exploration became a common theme in the early Space Race. Perhaps one of the most underappreciated yet vital components was the establishment of a global tracking and communication network. Stations were set up in various countries around the world, from Australia to Nigeria, to maintain contact with the orbiting spacecraft, receive telemetry data, and provide command capabilities. This network was a monumental feat of engineering and international cooperation in itself. Furthermore, advancements in life support systems, re-entry physics, and navigation techniques were crucial outcomes, laying the groundwork for future, more complex missions.

Navigating the Unknown

The path of Project Mercury was fraught with challenges. The intense pressure of the Space Race meant that schedules were tight, and the stakes were incredibly high. Every launch carried the weight of national prestige. Technical failures were a constant threat. Launch vehicle explosions during uncrewed tests were stark reminders of the power being harnessed and the potential for catastrophe. The astronauts themselves faced the unknown effects of weightlessness, radiation, and the psychological stresses of solo confinement in a tiny craft far from Earth. Could a human orient themselves? Could they eat, drink, and perform tasks without gravity? These were fundamental questions Mercury sought to answer, often through trial and error, with the ever-present risk of the ultimate price.

The Enduring Legacy of Mercury

Though relatively short-lived, the impact of Project Mercury was profound. It unequivocally demonstrated that humans could not only survive but also function effectively in the space environment. This was a critical prerequisite for the more ambitious Gemini and Apollo programs that followed. Mercury missions provided invaluable data on spacecraft design, launch operations, tracking, and recovery – lessons learned that were directly applied to subsequent efforts to reach the Moon. Beyond the technical achievements, Project Mercury captured the imagination of a nation and the world. It instilled a sense of pride and possibility, inspiring a generation to look towards careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The “Mercury Seven” became icons, their courage and pioneering spirit a lasting testament to human exploratory drive.

Perspectives: Then and Now

At the time, Project Mercury was viewed through a multifaceted lens. For many Americans, it was a source of immense national pride, a tangible demonstration of American capability in the face of Soviet dominance in the early Space Race. There was an palpable excitement, mixed with a degree of fear, given the inherent dangers. The astronauts were seen as modern-day explorers, pushing the boundaries of the known world. Internationally, while allies cheered American progress, the project was also undeniably a pawn in the Cold War, a display of technological prowess with clear geopolitical undertones.

Looking back, Project Mercury is recognized as a crucial, foundational step. Its spacecraft were rudimentary by later standards, its missions short. Yet, its significance cannot be overstated. It was the necessary learning curve, the proving ground that made everything that followed possible. It established operational procedures, built up engineering expertise, and, perhaps most importantly, fostered the belief that grander space exploration goals were achievable. The “Right Stuff” ethos associated with the Mercury astronauts also profoundly shaped the public image and expectations of spacefarers for decades to come, emphasizing bravery, technical skill, and an unwavering coolness under extreme pressure.

Project Mercury was more than just a series of rocket launches and capsule recoveries. It was an American confident, if sometimes uncertain, first stride into the cosmos. It answered the initial call of the Space Race, laid the vital groundwork for lunar ambitions, and transformed seven test pilots into enduring symbols of human courage and exploration. The echoes of Mercury triumphs and challenges resonate even today, a reminder of where the journey to the stars began for the United States.