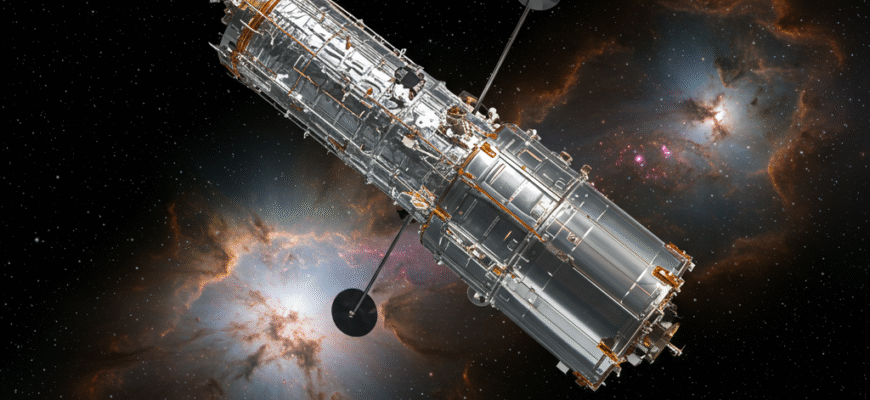

The Hubble Space Telescope, launched with immense global anticipation in April 1990, represented decades of scientific and engineering effort. It promised to revolutionize astronomy, offering an unprecedented view of the cosmos, free from the distorting haze of Earth’s atmosphere. However, shortly after its deployment, a profound and devastating flaw became apparent. The initial images returned by the multi-billion dollar observatory were fuzzy, a far cry from the sharp, groundbreaking pictures scientists had eagerly awaited. The world watched as NASA faced a crisis of monumental proportions; its flagship astronomical instrument was, in essence, partially blind.

A Flaw in the Making: Spherical Aberration

The culprit behind Hubble’s blurry vision was a subtle but critical error known as spherical aberration. The telescope’s magnificent 2.4-meter primary mirror, intended to be a perfect hyperboloid, had been ground to the wrong shape. It was too flat at its edges by a mere 2.2 microns – roughly 1/50th the width of a human hair. This minuscule imprecision meant that light rays reflecting off the outer regions of the mirror failed to converge at the same focal point as rays reflecting from the center. Instead of a single, sharp point of light, stars appeared as smeared blobs surrounded by hazy halos.

The discovery was a crushing blow. Years of meticulous planning, construction, and testing had somehow missed this fundamental defect. The implications were dire: Hubble’s ability to see faint, distant objects, one of its primary scientific goals, was severely compromised. The astronomical community and the public alike felt a wave of disappointment. The dream of a crystal-clear window to the universe seemed to have shattered.

The Genesis of a Solution: COSTAR

Despite the initial shock and the public relations nightmare, NASA and its engineers did not give up. The challenge was immense: how to fix a sophisticated optical instrument orbiting hundreds of miles above Earth? The answer lay in a remarkable piece of corrective engineering named COSTAR, which stands for Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement.

COSTAR wasn’t an imaging instrument itself. Instead, it was conceived as a set of “eyeglasses” for Hubble. Its ingenious design involved a system of small, precisely shaped mirrors that would intercept the flawed light beams from the main mirror and correct them before they reached three of Hubble’s original axial scientific instruments: the Faint Object Camera (FOC), the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph (GHRS), and the Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS). The Wide Field and Planetary Camera (WFPC), another key instrument, was slated to be replaced entirely by a new version (WFPC2) that had its own built-in corrective optics.

Designing COSTAR was an extraordinary feat. It had to fit into the slot originally occupied by another instrument, the High Speed Photometer. This meant it had to be roughly the size of a telephone booth and deploy its corrective mirrors with pinpoint accuracy once in orbit. The system consisted of a series of articulated arms, each holding tiny mirrors – some no larger than a coin – that would swing into the precise optical paths of the affected instruments. These mirrors were shaped with the inverse of the error in the primary mirror, effectively nullifying the spherical aberration.

The concept behind COSTAR was elegant: instead of attempting to repair or replace the massive primary mirror, a nearly impossible task in orbit, it introduced corrective elements into the telescope’s optical train.

This approach allowed for the restoration of Hubble’s intended capabilities for several key instruments.

The design required an incredibly detailed understanding of the exact nature of the primary mirror’s flaw.

This understanding was painstakingly derived from analyzing the blurry images Hubble initially produced.

The Daring Rescue: Servicing Mission 1 (STS-61)

The plan to install COSTAR and WFPC2 culminated in Servicing Mission 1 (SM1), executed by the crew of the Space Shuttle Endeavour (STS-61) in December 1993. This was one of the most complex and ambitious space repair missions ever attempted. It involved a record-breaking series of five lengthy spacewalks by astronauts who had trained intensively for years, practicing every maneuver in giant underwater mockups.

The astronauts, led by Commander Richard Covey and including Story Musgrave, Tom Akers, Kathy Thornton, Claude Nicollier, Jeff Hoffman, and Ken Bowersox, faced numerous challenges. They first had to carefully stow the original WFPC and the High Speed Photometer. Then, they meticulously installed the new WFPC2 and, crucially, COSTAR. The installation of COSTAR was particularly delicate. The device had to be slid into its bay, and then its tiny optical arms, carrying the corrective mirrors, had to be deployed. There was no room for error; the clearances were incredibly tight, and the components were fragile.

The world held its breath. The success of the mission, and indeed Hubble’s future, hinged on the astronauts’ skill and the flawless functioning of the corrective hardware. The spacewalks were grueling, pushing the limits of human endurance and capability in the harsh environment of space.

A Universe Reborn: The Impact of COSTAR

Weeks after the Endeavour crew returned to Earth, the first images from the refurbished Hubble began to arrive. The transformation was astounding. Gone were the fuzzy, indistinct blurs. In their place were razor-sharp, breathtaking views of distant galaxies, nebulae, and stars. The “before and after” images became iconic, vividly demonstrating the mission’s spectacular success. A collective sigh of relief, followed by cheers, erupted from NASA control rooms and astronomical observatories worldwide.

COSTAR had worked perfectly. The “eyeglasses” had restored Hubble’s vision to its intended acuity, and in some cases, even exceeded original expectations. The Faint Object Camera, now fed corrected light, could peer deeper into the cosmos than ever before. The spectrographs, also benefiting from COSTAR’s mirrors, could analyze the chemical composition and physical conditions of celestial objects with unprecedented precision.

The success of COSTAR and Servicing Mission 1 was a monumental triumph for NASA. It not only saved the Hubble Space Telescope but also restored faith in the agency’s capabilities. Hubble, now fully operational, began an era of unprecedented astronomical discovery. It provided crucial data on the age of the universe, the expansion rate of the cosmos, the existence of supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies, the birth of stars and planets, and the atmospheres of exoplanets.

The Legacy and Phasing Out of COSTAR

COSTAR was an essential, life-saving intervention for Hubble, but it was always intended to be a temporary measure for the first-generation axial instruments. As subsequent servicing missions took place, the original instruments that relied on COSTAR were gradually replaced by newer, more advanced instruments. These new instruments, such as the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) and the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), were designed with their own internal corrective optics, built to compensate for the primary mirror’s flaw directly.

With each replacement, fewer of COSTAR’s deployable arms were needed. Eventually, all three of the instruments it served had been superseded. During Servicing Mission 4 in May 2009, COSTAR itself was removed from Hubble to make way for a new scientific instrument, the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS). Its job done, the ingenious device was returned to Earth and is now displayed at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, a testament to one of the greatest feats of in-space repair.

The story of COSTAR is more than just a tale of technical ingenuity. It’s a story of perseverance, of refusing to accept failure, and of the incredible ability of human beings to solve complex problems. Without COSTAR, the Hubble Space Telescope might have been remembered as an expensive folly. Instead, thanks to this remarkable corrective device and the brave astronauts who installed it, Hubble became one of the most productive and influential scientific instruments ever built, forever changing our understanding of the universe.