The quest to measure the vast distances to the stars, a cosmic yardstick essential for understanding the universe’s scale, found a powerful ally in the burgeoning field of photography during the late nineteenth century. At the forefront of harnessing this new technology for the precise art of stellar parallax determination was Sir David Gill. His meticulous nature and unwavering commitment to accuracy transformed what was once an incredibly laborious and often frustrating task into a more systematic and reliable endeavor, laying crucial groundwork for much of twentieth-century astrophysics.

The Immense Challenge of Stellar Distances

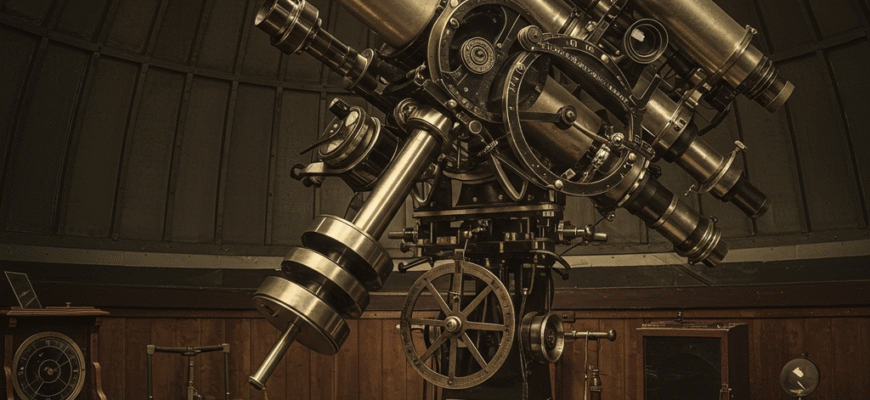

Stellar parallax, the apparent shift in a star’s position against a background of more distant stars as the Earth orbits the Sun, is a direct geometric method for measuring distance. The concept is simple, but the execution is extraordinarily difficult. The angular shifts involved are minuscule, typically less than one arcsecond – equivalent to discerning the width of a human hair from over 20 meters away. Before photography, astronomers relied on instruments like the filar micrometer attached to telescopes, or more specialized devices like the heliometer, to make these painstaking visual measurements.

These visual methods were fraught with challenges. They were incredibly time-consuming, requiring countless hours of intense observation at the eyepiece. Moreover, they were susceptible to “personal equation” – subtle, unconscious biases in how different observers perceived and recorded positions. Even the most skilled astronomers could produce slightly different results for the same star, introducing uncertainty into the precious data. The sheer effort meant that parallaxes for only a handful of the nearest stars had been determined with any degree of confidence by the mid-1800s.

David Gill: A Master of Precision

David Gill, who served as Her Majesty’s Astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope from 1879 to 1907, was a figure renowned for his dedication to precision. He wasn’t one to shy away from demanding observational programs if they promised a leap in accuracy. His early career saw him achieve remarkable success using the heliometer, particularly in determining a more accurate value for the solar parallax (the distance to the Sun) by observing the asteroid Iris in 1874 and later Mars in 1877. This work cemented his reputation as an astronomer capable of pushing the limits of existing instrumentation and techniques.

While Gill was a master of the heliometer, he was also keenly aware of its limitations and the potential offered by new technologies. The advent of the dry-plate photographic process in the 1870s presented an exciting opportunity. Unlike earlier wet-plate methods, dry plates could be prepared in advance, exposed for longer periods to capture fainter stars, and stored for later measurement in a controlled laboratory setting. This, Gill realized, could revolutionize parallax work.

Photography’s Dawn in Parallax Measurement

The advantages of photography for astrometry, and particularly for parallax determination, were compelling. Firstly, a photographic plate provided an objective and permanent record of a star field. Multiple stars could be captured on a single plate, and their relative positions measured at leisure, away from the pressures and discomforts of night-long telescope sessions. This greatly reduced the personal equation inherent in visual observations.

Secondly, long exposures could accumulate light from faint stars, making them measurable targets and, crucially, providing more distant, stable reference points against which the parallax of a nearer target star could be determined. The ability to measure many reference stars on the same plate also helped to average out small errors and improve the statistical reliability of the results.

Gill’s Photographic Campaigns at the Cape

Under Gill’s directorship, the Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope became a hub of innovation in astronomical photography. He recognized that simply taking pictures wasn’t enough; a rigorous methodology was required. Gill initiated ambitious photographic parallax programs, understanding that the key was a systematic approach to both taking the plates and measuring them.

The process involved taking a series of photographic plates of a target star field at specific times of the year, corresponding to the points in Earth’s orbit where the parallax displacement would be maximal in opposite directions (typically six months apart). To minimize systematic errors arising from instrumental flexure or atmospheric refraction changes, exposures were often made at similar hour angles. Careful attention was paid to the telescope’s focus and guiding.

Once developed, these plates were not simply eyed. They were measured using sophisticated measuring engines, essentially high-precision microscopes with finely calibrated screws, allowing the positions of star images to be determined to a tiny fraction of a millimeter. Gill and his team, notably including Jacobus Kapteyn who collaborated extensively on the measurement and reduction of plates for projects like the Cape Photographic Durchmusterung, developed and refined techniques for these measurements. The reduction of these measurements – the complex calculations required to convert plate positions into celestial coordinates and then into parallax values – was a formidable task in itself, demanding meticulous attention to detail.

Sir David Gill championed the use of photography for stellar parallax at the Cape Observatory. His systematic programs involved taking multiple plates of star fields at optimal times and then meticulously measuring them. This approach significantly increased the number of reliable parallax measurements, especially for southern hemisphere stars, and demonstrated the superiority of photographic methods over older visual techniques for this demanding work.

One of Gill’s significant early photographic parallax results involved a set of 22 southern stars, published around the turn of the 20th century. These results were obtained using the Astrographic Telescope at the Cape, an instrument designed for the international Carte du Ciel project, but which Gill also astutely applied to parallax work. He meticulously compared stars on plates taken at different epochs. For instance, plates of Alpha Centauri, our nearest stellar neighbor, and other bright southern stars were taken and measured with the highest possible precision. His insistence on multiple exposures on each plate, and multiple plates for each star, helped to identify and reduce both random and systematic errors.

The challenge was not just in taking the photographs but in ensuring the stability of the photographic emulsion and the accuracy of the measuring process. Gill investigated potential sources of error, such as optical distortions in the telescope, changes in the plate scale, and the effects of temperature on the measuring instruments. His approach was holistic, considering every step from the telescope pier to the final calculated parallax.

The Enduring Impact of Photographic Parallax

David Gill’s pioneering use of photography for stellar parallax had a profound impact. It demonstrated conclusively that photographic methods could yield parallaxes with greater accuracy and efficiency than visual techniques for a larger number of stars. The objectivity of the photographic plate was a game-changer. While the heliometer, in the hands of a master like Gill, could produce excellent results for bright stars, photography opened the door to studying fainter and more numerous stars.

His work at the Cape served as a model for other observatories worldwide. The success of his programs encouraged the wider adoption of photographic techniques for astrometry. This, in turn, led to large-scale parallax surveys in the early 20th century, such as those undertaken at Allegheny Observatory, McCormick Observatory, and Yerkes Observatory. These surveys dramatically increased the catalogue of stars with known distances, providing the essential data for studying the structure and kinematics of the local Milky Way galaxy.

Gill’s contributions went beyond just the numbers. He fostered a culture of precision and critical analysis. He understood that reliable data was the bedrock of astronomical progress. His application of photography to the difficult problem of stellar parallax was not merely a technological switch but a paradigm shift in how astronomers approached the measurement of the cosmos. It was a critical step in transforming astronomy into a truly quantitative science, paving the way for our modern understanding of stellar populations and galactic structure. The legacy of David Gill is not just in the specific parallaxes he measured, but in the rigorous, systematic, and innovative approach he brought to this fundamental astronomical challenge.