The ancient Egyptians looked to the vast, star-dusted expanse above them not merely as a canopy of night, but as a divine realm, a celestial Nile teeming with gods, spirits, and perilous journeys. For them, the afterlife was not a static paradise passively entered, but a dynamic voyage requiring guidance, knowledge, and often, a skilled boatman. This figure, the celestial ferryman, became a crucial character in their intricate tapestry of sky myths, a navigator of cosmic waters who held the key to traversing the boundary between the mortal world and the eternal realms, or between different phases of divine existence.

The Cosmic Waterways Above

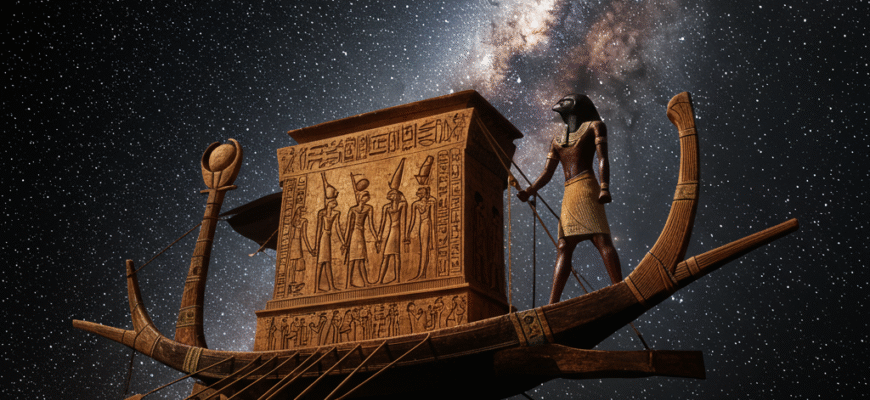

To understand the ferryman’s role, one must first appreciate the Egyptian conception of the cosmos. The sky, often personified by the goddess Nut, was frequently envisioned as a great, navigable ocean, sometimes called the ‘Winding Waterway’ or seen as an extension of the primordial waters of Nun from which all creation emerged. Just as the terrestrial Nile was the lifeblood of Egypt, its celestial counterpart was the path for gods and blessed souls. The sun god Ra himself journeyed across this sky-ocean daily in his magnificent barque, a voyage that symbolized the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. This journey was fraught with challenges, from monstrous serpents like Apep to treacherous shoals and gates guarded by fearsome entities.

The Duat, the underworld or realm of the dead, was also intricately connected to these celestial pathways. While sometimes depicted beneath the earth, it was also the realm through which Ra sailed during the night hours, bringing light and regeneration to those who resided there before his glorious rebirth at dawn. For the deceased, particularly the pharaoh and later, common Egyptians who could afford the funerary rites and texts, the aspiration was to join Ra on his solar boat or to navigate these waters to reach the Field of Reeds, a blissful afterlife. But this passage was not automatic; it required a vessel and, critically, a ferryman.

Navigating the Perils of the Sky

The journey was not for the faint of heart or the unprepared. The celestial waters held numerous obstacles. There were lakes of fire, challenging gatekeepers, and currents that could lead one astray. Without a guide, a soul could be lost, or worse, fall prey to a ‘second death’, an utter annihilation from which there was no return. The ferryman was thus more than a simple boat operator; he was a gatekeeper, a guide, and sometimes a judge of worthiness. His boat was the sacred vessel that could safely traverse these mystical landscapes, often imbued with its own magical properties.

Meet the Celestial Navigators

Several figures appear in Egyptian texts fulfilling the role of the celestial ferryman, each with unique characteristics and specific domains. Their existence underscores the perceived difficulties of the journey and the need for specialized divine assistance. These figures were not always benevolent or easily swayed; they often required payment, specific knowledge, or even threats from the deceased, who might invoke their own divine power or affiliations.

Aken: The Grumbling Guardian

One of the most prominent and perhaps earliest mentioned ferrymen is Aken. His name is thought to mean ‘The Protector’ or ‘The Watcher’. Aken often appears in the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead, specifically associated with ferrying souls across the Lily Lake or other waters of the Duat to reach the domain of Osiris or the Field of Reeds. He is characteristically portrayed as reluctant, sometimes even asleep, and needing to be awakened and persuaded to perform his duties. The deceased would have to address him with specific incantations, proving their purity and knowledge of sacred names and spells.

Aken’s role was critical; he was the guardian of the ferryboat, and without his cooperation, the soul was stranded. The texts provide formulae for the deceased to declare their innocence of wrongdoing, asserting they are ‘pure’ and worthy of passage. Sometimes, the deceased had to list the parts of the boat, naming them correctly, to prove their ritual understanding. Aken’s reluctance might symbolize the inherent difficulty of the transition, a test of the soul’s resolve and magical preparedness.

Mahaf: The Vigilant Helmsman

Another significant ferryman is Mahaf, whose name means ‘He Who Looks Behind Him’. This intriguing name suggests a constant vigilance, perhaps looking back to ensure the safety of his passenger or looking back at the mortal coil being left behind. Mahaf is frequently mentioned as the ferryman who rows the sun god Ra across the sky or through the Duat in the solar barque. By extension, he also serves the deceased king or worthy soul who seeks to join Ra’s retinue.

Mahaf is generally depicted as more active and less obstructive than Aken. He is part of the divine crew of Ra and his role is integral to the cosmic order. The deceased wishing to cross with Mahaf might need to identify themselves with Horus or another deity, or to provide the ‘fare’ – not in a monetary sense, but in terms of magical power or justification. He is a figure who understands the profound journey being undertaken, navigating not just physical space but the very fabric of time and existence as he steers the boat through the hours of the night towards dawn.

The celestial ferrymen, such as Aken and Mahaf, were not mere boatmen in Egyptian mythology. They were pivotal figures in the soul’s post-mortem journey and the sun god’s cyclical voyage. Their consent and skill were essential for navigating the treacherous waters of the Duat and the sky. Access to these ferrymen often depended on the deceased’s ritual purity, magical knowledge, and ability to recite powerful spells.

The Solar Barque and Its Divine Crew

The most iconic celestial vessel is undoubtedly the solar barque of Ra. This divine ship had two forms: the Mandjet boat, which carried Ra across the daytime sky, and the Mesektet boat, which transported him through the Duat during the night. This journey was a daily drama of cosmic significance, ensuring the sun’s reappearance and the continuation of life. The crew of the solar barque consisted of various deities who helped navigate, protect Ra, and overcome adversaries like Apep.

The deceased pharaoh, and later other blessed dead, aspired to join this divine crew or to have their own passage mirror Ra’s triumphant journey. The ferryman, in this context, was part of this divine machinery, ensuring the smooth operation of cosmic law. Becoming a passenger on such a vessel was the ultimate mark of a transfigured spirit, an Akh, who had successfully navigated the trials of judgment and was now part of the eternal, cyclical nature of the cosmos.

The Journey of Ra as a Blueprint

Ra’s nightly voyage through the Duat was a blueprint for the deceased. Each hour of the night corresponded to a different region of the Duat, with unique challenges and deities. Successfully passing through these with Ra meant revitalization and rebirth with him at dawn. The ferryman was thus a key enabler of this process, whether it was Mahaf at the helm of Ra’s own boat or another ferryman guiding the individual soul on a parallel path towards light and renewal.

Spells and Passage: The Deceased’s Plea

The Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts, and the Book of the Dead are rich sources of spells and utterances designed to secure passage across the celestial waters. These texts demonstrate the profound anxiety and hope associated with this journey. The deceased often had to address the ferryman directly, stating their name, their divine parentage (real or adopted through ritual), and their blamelessness.

A common theme is the ‘knowledge of names’. Knowing the true name of the ferryman, the boat, its oars, its mooring posts, and even the river itself, conferred power over them. For example, Coffin Text Spell 397 is specifically titled ‘Spell for bringing the ferry-boat’ and involves a dialogue where the deceased must identify parts of the boat to Aken. If the ferryman was reluctant, some spells provided the deceased with the authority to command him, sometimes even threatening to report him to higher gods like Ra or Osiris.

This interaction highlights a fascinating aspect of Egyptian religious thought: the power of words and knowledge. The journey to the afterlife was not solely about moral purity, though that was important; it was also about possessing the correct ritual and esoteric understanding. The ferryman acted as a litmus test for this sacred Gnosis.

Beyond the Boat: Symbolism of the Ferryman

The celestial ferryman is more than just a mythological character; he embodies profound symbolism. He is a liminal figure, standing at the threshold between worlds – life and death, chaos and order, darkness and light. His boat is the vehicle of transformation, carrying souls from a state of mortality to one of divinity and eternity. The act of crossing the water represents a rite of passage, a purification, and an entry into a new state of being.

The ferryman’s occasional reluctance or the need for payment (in the form of spells or justification) underscores the idea that passage to the blessed afterlife is not an entitlement but something to be earned or skillfully negotiated. He ensures that only the worthy, the knowledgeable, and the pure make the crossing, maintaining the sanctity of the divine realms. In a universe governed by Ma’at (truth, balance, order), the ferryman is an agent of this cosmic principle, ensuring that the transitions within the cosmos proceed according to divine law.

Ultimately, the celestial ferryman in ancient Egyptian sky myths represents hope and continuity. He is the indispensable guide who makes possible the journey towards light, rebirth, and eternal existence among the gods and stars. Without him, the soul would be adrift, and even the sun god’s vital journey could be imperiled. His oar strokes through the cosmic waters echo the enduring human aspiration to transcend mortality and navigate the mysteries of existence.