The vast, largely uncharted celestial tapestry of the Southern Hemisphere beckoned. While the northern skies had been meticulously scrutinized by astronomers for centuries, culminating in the groundbreaking work of William Herschel, the southern expanse remained a realm of relative mystery. It was this very void, this grand incompletion of humanity’s map of the cosmos, that spurred his son, John Herschel, to embark on one of the most ambitious astronomical expeditions of the 19th century.

John Frederick William Herschel was not merely riding on his father’s coattails. A brilliant mind in his own right, a mathematician, chemist, and inventor, he possessed the intellectual rigor and the passionate curiosity essential for such a monumental task. He saw it as a filial duty, a completion of the survey his father had so masterfully begun, to extend the systematic “sweeping” of the heavens to the stars visible only from below the equator.

A Voyage to the Cape

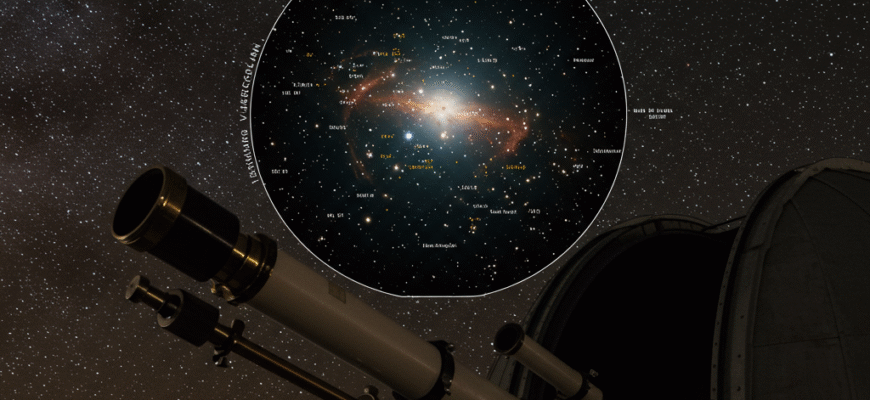

The decision was made: the Cape of Good Hope, with its favorable southern latitude and relatively stable atmospheric conditions, would be the destination. In 1833, John Herschel, accompanied by his family, embarked on the long sea voyage. This was no casual trip; he transported not only his household but also the components of his powerful reflecting telescopes, including a massive 20-foot focal length instrument, a near-twin to the one his father had used to revolutionize astronomy.

Upon arrival in early 1834, the immediate challenge was finding a suitable location. He selected an estate called ‘Feldhausen’ in Claremont, a few miles from Cape Town, nestled against the eastern slopes of Table Mountain. Here, amidst vineyards and orchards, he began the arduous process of constructing his observatory. This wasn’t just about assembling a telescope; it involved building stable foundations, protective housing, and the intricate machinery needed to maneuver the colossal instrument skyward.

Sweeping the Southern Skies

For four intense years, from 1834 to 1838, John Herschel dedicated himself to a systematic survey of the southern sky. Night after night, weather permitting, he would be at the eyepiece of his 20-foot reflector, or his smaller 7-foot refractor, meticulously “sweeping” pre-planned zones of the sky. His method, inherited and refined from his father, involved slowly moving the telescope in declination while he scanned back and forth in right ascension, calling out observations to an assistant who recorded them.

The sheer scale of the undertaking was immense. He was not just looking for new objects; he was re-observing known ones with greater precision, describing their appearance, measuring positions, and attempting to understand their nature. The southern sky offered a dazzling array of celestial wonders largely unseen from Europe: the Magellanic Clouds, globular clusters like Omega Centauri and 47 Tucanae, and the rich star fields of the Milky Way towards the galactic center.

His nights were a dance with the cosmos. He sketched what he saw, his drawings of nebulae becoming iconic for their detail and accuracy. He battled fatigue, the occasional challenging weather – the ‘Cape Doctor’ wind could be fierce – and the technical difficulties inherent in operating such large, delicate instruments far from the established scientific centers of Europe. The mirrors of his reflectors, made of speculum metal, tarnished easily in the Cape air and required frequent, laborious re-polishing, a task he often undertook himself. The isolation, in some ways, was a boon, allowing for focused work, but it also meant he was largely on his own for troubleshooting and innovation.

Unveiling Southern Treasures

Herschel’s Cape observations yielded a treasure trove of data. He cataloged thousands of new double stars, discerning their colors and relative positions, contributing significantly to the understanding of binary systems and stellar masses. He discovered or re-observed and meticulously described 1,707 nebulae and star clusters, a monumental addition to the known celestial objects. His detailed studies of the Magellanic Clouds were particularly groundbreaking, revealing their complex structures and stellar populations. He was among the first to suggest they were not simply nebulous patches but independent star systems, galaxies in their own right, though the term “island universes” was yet to be widely accepted. His meticulous star counts in different directions, extending his father’s work, also provided further evidence for the flattened, disc-like structure of our own Milky Way galaxy, and helped to better estimate its extent, particularly towards the densely populated southern regions.

His observations of the Eta Carinae nebula were also remarkable. He documented its intricate details and the extraordinary variability of the central star, which was then undergoing a period of brightening that would make it one of the brightest stars in the sky. He also made significant observations of Halley’s Comet during its 1835 apparition, providing valuable data on its structure and behavior.

John Herschel’s four-year stint at the Cape resulted in the cataloging of 1,707 nebulae and clusters, and 2,102 double stars. This systematic survey effectively doubled the number of known nebulae at the time. His comprehensive work laid a robust foundation for all subsequent studies of the southern celestial sphere.

Beyond the Stars: Photography and Botany

While astronomy was his primary mission, Herschel’s insatiable curiosity extended to other scientific fields during his time at the Cape. He was a pioneer in photography, experimenting with chemical processes. It was during this period, or shortly after, that he coined the terms “photography,” “negative,” and “positive,” and discovered that hyposulfite of soda (hypo) could be used as a “fixer” to make images permanent – a crucial step in the development of the photographic process. He even used a camera lucida to sketch the South African landscape and its unique flora, contributing to botany with his detailed illustrations.

The “Results” and Enduring Impact

In 1838, John Herschel and his family returned to England, bringing with them an unparalleled collection of astronomical data. The subsequent years were dedicated to the colossal task of reducing, analyzing, and preparing this information for publication. This culminated in the 1847 release of his magnum opus: “Results of Astronomical Observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope.” This volume was a landmark in astronomical literature, providing the first comprehensive and systematic catalog of the southern skies.

His work didn’t just add numbers to a list; it provided detailed descriptions, classifications, and insights that shaped astronomical understanding for decades. It completed the global survey initiated by his father, William, and his aunt, Caroline. For his contributions, John Herschel was showered with honors, including a baronetcy.

The legacy of John Herschel’s Cape observations is profound. He effectively opened up the southern sky to detailed scientific inquiry, providing the foundational data upon which much of modern Southern Hemisphere astronomy is built. His meticulous catalogs are still referenced, and his pioneering spirit continues to inspire. The observatory he established, though long gone, is commemorated by an obelisk in Claremont, a silent testament to a man who ventured south to complete humanity’s view of the universe, and in doing so, vastly expanded our cosmic horizons.

His dedication was not just to the act of discovery, but to the careful, systematic recording and sharing of knowledge. This commitment ensured that his four years under the southern stars would illuminate the path for generations of astronomers to come, forever changing our understanding of the grand celestial sphere that envelops us.