Few tales whispered down from the ancient world possess the quiet, dreamlike allure of Endymion and Selene. It is a story steeped in moonlight, eternal youth, and a love that bridges the celestial and the terrestrial. The shepherd, or perhaps king, Endymion, blessed (or cursed) with everlasting sleep and ageless beauty, becomes the object of adoration for Selene, the luminous goddess of the Moon. Night after night, she would descend to Mount Latmos to gaze upon his serene face, a silent vigil that has captivated artists for centuries. This myth, with its potent blend of beauty, desire, and the enigma of eternal slumber, has proven to be a remarkably fertile ground for artistic imagination, its depictions shifting like the phases of the moon itself across different eras and cultural landscapes.

The Whispers of Mount Latmos: Unpacking the Myth

The figure of Endymion is somewhat fluid in classical accounts. Most commonly, he is a shepherd of exquisite beauty residing on Mount Latmos in Caria. Other traditions paint him as a king, or even an astronomer who, by observing the moon’s cycles, gained Selene’s favor. Regardless of his mortal station, his defining characteristic became his unparalleled handsomeness, so profound it ensnared a goddess. Selene, often identified with Artemis or Diana in later syncretism but distinctly the Titan personification of the Moon in earlier myths, was struck by an irresistible love for the sleeping mortal.

The core of the narrative revolves around Selene’s nocturnal visits. Overwhelmed by his beauty, she implored Zeus to grant Endymion a wish. The most common version holds that Endymion himself chose eternal sleep, thereby preserving his youth and beauty indefinitely, allowing Selene to visit him undisturbed for all time. However, variations exist: some suggest Selene orchestrated this eternal slumber to keep him forever young and exclusively hers, a divine possessiveness veiled in a seemingly gentle act. This ambiguity – a willing embrace of oblivion versus a divinely imposed stasis – adds a layer of complexity to the myth, making Endymion a figure of both perfect peace and profound passivity.

Mount Latmos, the traditional setting, becomes more than just a geographical location; it transforms into a sacred, liminal space where the divine and mortal intersect, where time itself seems to pause under the moon’s tender gaze. It is here that Selene, in her chariot drawn by white horses or oxen, would alight, her divine radiance illuminating the sleeping youth. Some traditions even speak of their union producing fifty daughters, the Menae, personifications of the fifty months of the Olympiad, further cementing the myth’s connection to time and cycles.

Echoes in Stone and Pigment: Antiquity’s Embrace

The story of Endymion and Selene found particularly poignant expression in the art of the Roman world, most notably on sarcophagi. These funerary monuments, designed to house the remains of the deceased, frequently featured the myth, transforming it into a powerful symbol of hope and solace. The depiction of Endymion, eternally young and peacefully asleep, offered a comforting vision of death not as an end, but as a serene, dreamlike state. Selene’s descent to her beloved became an allegory for a love that transcended the grave, a divine care extending into the afterlife.

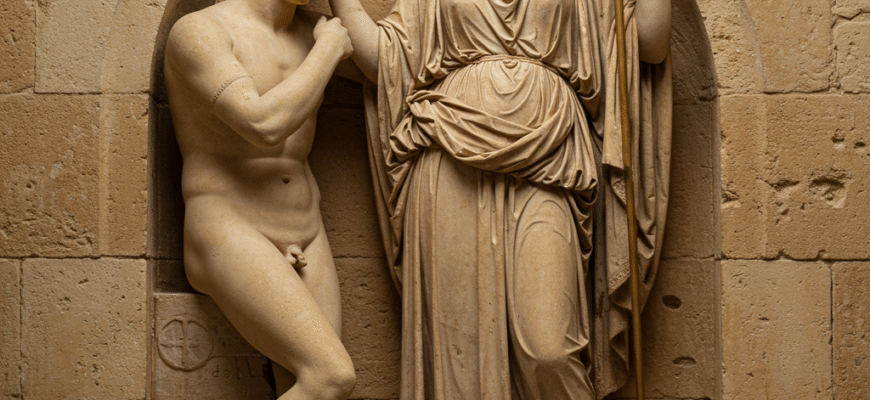

Typical iconography on these sarcophagi shows Selene, often draped and majestic, stepping down from her chariot or simply approaching the recumbent Endymion. He is invariably depicted as a handsome youth, relaxed in slumber, sometimes accompanied by his hunting dog or a pastoral staff, hinting at his shepherd origins. Small Erotes or Cupid figures might flit around, underscoring the theme of love, while Hypnos, the personification of sleep, sometimes appears, gently touching Endymion. The mood is one of profound stillness, an idealized beauty captured in marble, offering a vision of eternal peace rather than sorrow.

Beyond sarcophagi, the myth also appeared in Roman frescoes, such as those unearthed in Pompeii, and in mosaics. These depictions, while perhaps less overtly funereal, still carried connotations of divine love and the power of beauty. The visual language remained consistent: a focus on the grace of Selene and the tranquil beauty of Endymion, often set within an idyllic landscape. These ancient portrayals established a visual tradition that would resonate for centuries, emphasizing the gentle, almost reverent nature of Selene’s love.

The consistent portrayal of Endymion in a state of peaceful, youthful slumber on Roman sarcophagi underscores a deep-seated desire for a serene afterlife. Selene’s gentle approach, often accompanied by figures like Hypnos (Sleep) or Amor (Love), further frames the scene not as a violation but as a tender, eternal union. This imagery offered comfort and a vision of beauty persisting beyond mortality, reflecting a cultural longing for peaceful transition. The motif’s recurrence speaks volumes about its consolatory power in Roman funerary art.

Renaissance and Baroque: A Reawakening of Passion

With the Renaissance came a fervent rediscovery of classical antiquity, and the myths of Greece and Rome once again became central subjects for artists. Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” and other classical texts provided rich narrative sources, and the tale of Endymion and Selene, with its themes of love, beauty, and divine encounter, was readily embraced. Renaissance artists, captivated by the human form and the ideals of classical beauty, often depicted Endymion with an emphasis on his physical perfection, sometimes echoing the sensuality of ancient sculpture. Selene, too, was rendered with grace and majesty, her divine nature apparent.

The settings became more lush, the compositions more complex, reflecting the era’s artistic innovations. While still retaining a sense of idealization, there was a growing interest in the psychological and emotional dimensions of the myth, moving beyond the purely symbolic interpretations common in antiquity. The focus often remained on the tender moment of Selene’s discovery or her gentle approach, but infused with a new appreciation for human emotion and naturalistic representation.

The Baroque Drama Unfurls

The Baroque period, succeeding the Renaissance, took the emotional intensity and dynamism to new heights. If Renaissance art celebrated classical harmony, Baroque art reveled in drama, movement, and theatricality. The story of Endymion and Selene provided ample opportunity for such displays. Artists of this era often chose to depict the very moment of Selene’s descent, her arrival charged with divine power and palpable desire. Strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) heightened the drama, with Selene, perhaps bathed in celestial light, illuminating the deeply shadowed, sleeping Endymion.

Compositions became more dynamic, with swirling drapery, dramatic gestures, and a sense of immediacy. Endymion’s vulnerability in sleep was often contrasted with Selene’s active, almost commanding presence. Figures like Nicolas Poussin, for instance, in his mythological landscapes, often imbued such scenes with a potent mix of classical order and baroque energy, though specific, widely known Endymion pieces by the top-tier Baroque masters are less iconic than, say, their Bacchanals. However, the general spirit of the Baroque – its love for grand narratives and emotional expression – certainly colored interpretations of the myth, emphasizing the passion of the goddess and the helplessness of the mortal. The scene became a stage for divine intervention, rendered with a richness of color and texture that appealed directly to the senses.

Neoclassical Serenity and Romantic Longing

As the exuberance of the Baroque waned, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the rise of Neoclassicism, a movement that sought to return to the perceived purity, clarity, and noble simplicity of classical art. This shift in aesthetic sensibility profoundly influenced the depiction of Endymion and Selene.

The Purity of Form: Neoclassicism

Neoclassical artists admired the idealized forms and serene beauty of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. The figure of the sleeping Endymion, with its inherent stillness and grace, became a perfect subject. Perhaps the most famous Neoclassical rendition is Antonio Canova’s marble sculpture, “The Sleeping Endymion” (completed 1819-1822). Canova’s Endymion is the epitome of idealized male beauty, his form smooth, his pose relaxed and elegant, conveying an almost unearthly tranquility. There is little of the overt passion of Baroque interpretations; instead, the focus is on the perfection of form, the quietude of eternal sleep. Selene is often absent or merely implied, the emphasis being entirely on Endymion as an aesthetic object, a personification of peaceful, beautiful slumber. The mood is contemplative, an homage to classical ideals of balance and harmony.

The Dreamer Awakens: Romanticism’s Gaze

Following closely on the heels of Neoclassicism, and sometimes overlapping with it, Romanticism offered a different lens through which to view the myth. Romantics were drawn to emotion, individualism, the sublime, mystery, and the power of dreams. The moon itself was a potent Romantic symbol, associated with melancholy, longing, and the ethereal. John Keats’ epic poem “Endymion” (1818) became a cornerstone of Romantic literature, profoundly shaping the perception of the myth. Keats’ Endymion is not merely a passive sleeper but a dreamer, a seeker of ideal beauty and transcendent love, embarking on a spiritual quest.

Visually, Romantic interpretations often emphasized the atmospheric and the emotional. The landscape of Mount Latmos might become wilder, more evocative of nature’s sublime power. Selene could be portrayed as a more distant, ethereal figure, her light casting a mysterious glow. Endymion, even in sleep, might seem to be experiencing profound dreams or longings. The focus shifted from purely physical beauty to the inner world, the landscape of the soul. Artists like Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, with “The Sleep of Endymion” (1791), bridged Neoclassical form with a nascent Romantic sensibility, imbuing the scene with a dreamlike, almost erotic quality.

Victorian Visions and Beyond

The fascination with Endymion and Selene continued throughout the 19th century. Victorian artists, often drawn to classical subjects, revisited the myth, sometimes imbuing it with the era’s characteristic sentimentality or a more overt moral or allegorical meaning. The Pre-Raphaelites and their associates, with their love for detailed realism and themes of love and beauty, found resonance in the tale. George Frederic Watts, for example, created several versions of “Endymion,” depicting him with an ethereal, spiritualized beauty, reflecting the Symbolist tendencies that emerged towards the end of the century.

Symbolist painters, in particular, were attracted to the myth’s inherent mystery and its potential to explore themes of the unconscious, the soul’s longing for the divine, or the interplay between dream and reality. Selene could become a symbol of the elusive ideal, and Endymion the eternally searching human spirit. The visual language often became more suggestive and less literal, focusing on mood and atmosphere to evoke a sense of otherworldly beauty and profound introspection.

While the myth of Endymion and Selene may not be as overtly prominent in contemporary art as it once was in previous centuries, its core themes – the allure of eternal beauty, the nature of love and desire, the mystery of sleep and dreams, and the encounter between the human and the divine – remain timeless. The sleeping shepherd, forever young on his moonlit mountain, and the devoted goddess who watches over him, continue to hold a place in our cultural imagination. Their story, filtered through the diverse artistic visions of countless generations, stands as a testament to the enduring power of myth to inspire and to be perpetually reinterpreted, each depiction reflecting the values and anxieties of its own time while touching upon universal human experiences. The quiet romance on Mount Latmos still whispers to us across the ages, a soft luminescence in the vast gallery of human creativity.